Into the Kalahari - Part 1

Tracks Across Botswana #1

Earlier this year we drove nearly 4,000 km across Botswana. For a month, we camped in some of the great wilderness areas ofAfrica. We brought back journals full of stories. This is the first in a series—“Tracks Across Botswana”—from the trip.

A twin track “road” snaked ahead of us up and over ancient sand dunes. On either side, Kalahari apple leaf and black acacia thickets crowded in, dense and unyielding. The Hilux slid through the hot red sand, growling deeply in first gear as the steering wheel jerked from side to side fighting with the deep grooves in the road. It had been six relentless hours behind the wheel—much of that to the tune of an awful screeching noise, like nails on a chalkboard, as inch long acacia thorns scraped paint off the doors.

Completely self-reliant, we were loaded with enough fuel and supplies for a week. We carried a satellite phone for the worst case scenario and a bottle of whiskey for the scenario worse than that. I tell myself that the best things in life don’t yield easily. But this didn’t squash the lingering sense of apprehension as we pushed deeper into the central Kalahari, one of Africa’s last true wildernesses.

The Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) is immense. Ten percent of Botswana and larger than the Netherlands. It’s a difficult landscape. Inaccessible and hostile. Summer days are an inferno and winter nights are below freezing. It receives just too much rain to be considered a true desert, yet any moisture is almost immediately evaporated by the relentless sun.

It endures, largely untouched by people, partly because it can look after itself. No rangers, scientists or careful intervention. It’s scale allows for self regulation. In much of Africa, wild places have been bent or broken—commercialised, compromised, diminished. But not here.

Part of its defense is its own geology. One hundred million years ago, ancient rivers left behind a sea of thick Kalahari sand. That sand still holds. It swallows the tiny road network, slows progress, and keeps most of the reserve unreachable. What’s left is wilderness on its own terms. And it is a true wilderness. There are just a few sandy 4x4 tracks and a handful of designated areas to camp. There is no water, no food and a great big indemnity form at the entrance “gate” – just an outpost with an access boom reached after hours of driving in deep sand. You have to look after yourself here.

At last we crested a final dune and, like a mirage, Pipers Pan emerged shimmering in the late afternoon heat. An ancient dried up lake, its huge, flat, grassy expanse stretched far into the distance. The road immediately hardened, the incessant screeching of thorns on the car stopped. It felt like we had been descending a staircase to the underworld only to open the door to paradise.

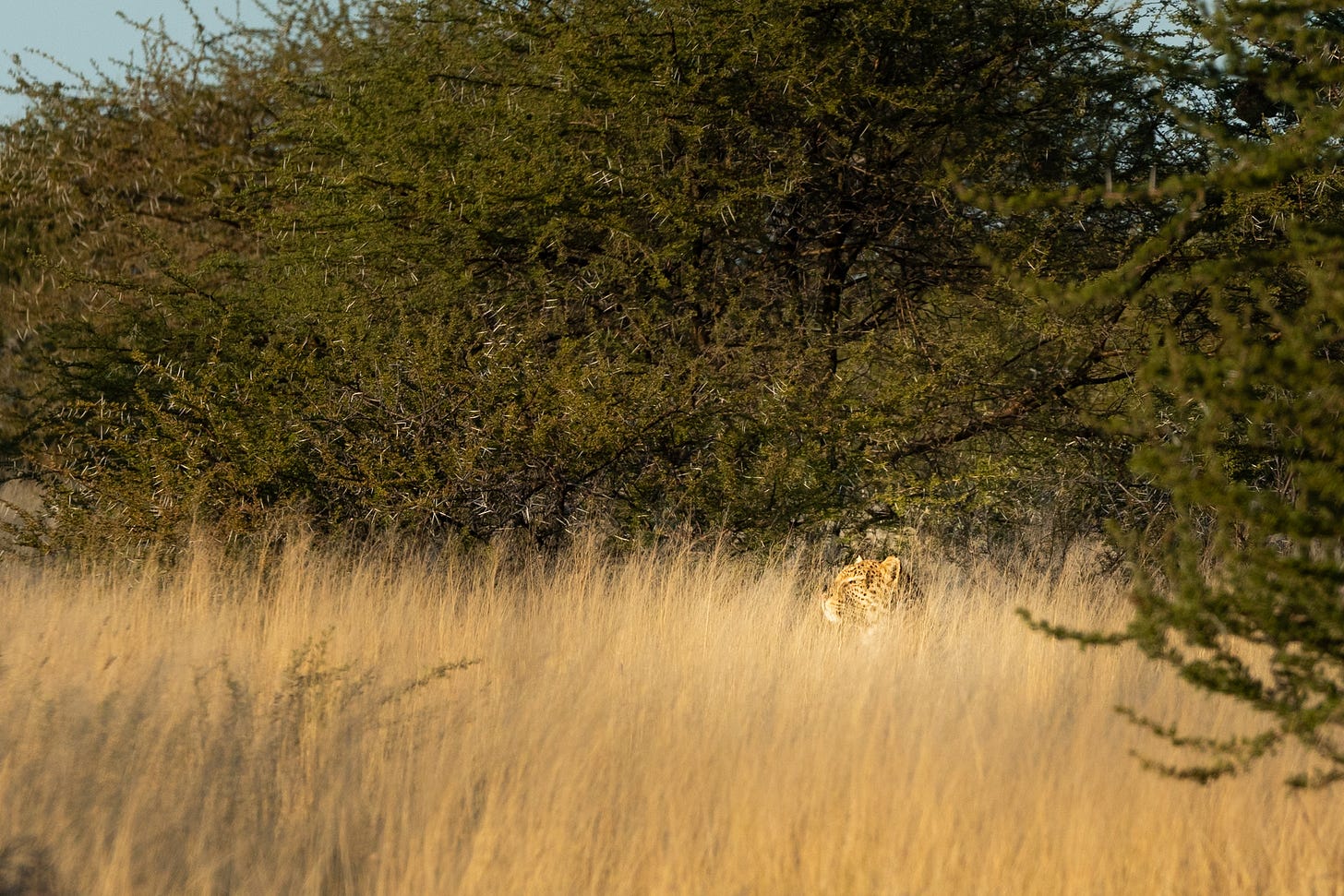

Herds of springbok—small gazelles with inward turned horns—dotted the pan. Their faces were boldly painted in black and white, theatrical, marionette like. There were ostriches, wildebeest, gemsbok. Great herds of them feasting on the rich grassland. Some are sedentary (they don’t leave the CKGR) others make their way here from across Botswana to fatten up on the sweet, nutritious grass. Where the herds are, the large predators follow. Lion, leopard, cheetah, jackal and brown hyena are all Kalahari specialists.

We stopped the car and got out on the edge of the pan. Other than a curious glance, the animals were unfazed by us. To quote Mark and Delia Owens (the same Delia Owen’s of “Where the Crawdads Sing” fame) from their iconic book Cry of the Kalahari:

Here was a place where creatures did not know of man’s crimes against nature.

We were now more than 50 kilometres from any other person—200 kilometres or more from any kind of permanent habitation. We would not see another person until we left this place a few days later.

It’s true that the animals are much wilder here. They see less people and don’t associate us with hunting or poaching. But that doesn’t mean that we haven’t inflicted wide scale harm. Not too long ago the herds of the Kalahari numbered in the millions, migrating north and south at the change of season. But, through the 80’s, the government built large veterinary fences across Botswana to “protect” the burgeoning beef industry from wild animal borne diseases. There is no evidence that this worked. The result on the wildlife though was devastating. Cut off from their migration routes, the great herds could not escape the dry season. Numbers collapsed catastrophically.

But the land and the animals remember. As the fences fall into a state of disrepair, the ancient routes reopen. Slowly, the herds are returning.

We set up the campsite at dusk on a hill at the back of the pan and built a large fire. Quickly, in the sudden African transition from dusk to night, all colour leached away from the trees and darkness shut down in a close circle about us. The flickering red light of the fire, an ancient primal comfort pushing back against the darkness. Nights in the Kalahari belong to its predators.

We watched the flames, the phantoms and faces flickering over the wood. Above us, the haunting “hoo, hooo” of the Spotted Eagle owl. Below us on the pan, the loud mournful cry of the black-backed jackel. To the north, faint but clear, the guttural roar of a male lion built to a crescendo before tapering out into a series of staccato coughs.

We sat in silence contemplating our isolation. Its an immersive, soul stirring feeling. A reminder that we too are part of this world not apart from it. All of our petty striving seems insignificant against this untamed wilderness. If all people, even those who have known nothing but the crowded, concrete jungle of cities, could visit a place like this, then perhaps they would return to their lives cleansed and refreshed, their subsequent ambitions more attuned to the grounding effect of nature. It’s a nice thought. Naïve perhaps, but nice.

Eventually, our fireside philosophy exhausted, we turned in for the night, scrambling up ladders to our rooftop sanctuaries. The sound of the African night was the perfect lullaby.

To be continued..

Until next time.

I really thought about the book Cry of the Kalahari while reading your essay. You will never forget the Kalahari desert .

Great reading… great description of the long difficult road but rewarded by all this wild animals and a beautiful landscape of Africa

Looking forward for part 2

Oh, this brings back memories...